“Atomic” Messages: Stamps, Seals, and Postal Envelopes as Archival Sources

Loukas Freris

Working on the history of radiation protection in Greece, about a year ago I went to the apartment of Alexios Spanidis, son of the first president of the Greek Atomic Energy Commission and the Nuclear Research Center “Demokritos,” Athanasios Spanidis, in order to interview him. After the end of the interview, we had—as usual—an off-the-record conversation. During this small talk, I asked him if he had kept any material from his father’s archival records, a question that was crucial to my research since in Greece there are no organized archives on the country’s nuclearization. Thus, a positive response by Spanidis was likely to completely change the course of my research, as had already happened once.

However, in this case I did not expect much. After all, I knew that the archive of Athanasios Spanidis is kept in the Greek Literary and Historical Archive (ELIA). And indeed, I received the obvious answer that whatever archival material he’d had in his possession he had given to that archive, where it is freely accessible to the public. In response to my next question, however, I received two ‘gifts.’ After explaining to Spanidis that I knew about these files and had already studied them, I asked him if he perhaps had any photos—since at ELIA I had seen many documents, but no photographs whatsoever.His answer was the first gift. Of course he’d had photos and of course he had given them to the same archive. He was right! When—skeptically—I visited ELIA again and asked to see the photos from the Spanidis archive, I was informed that their photo archive is located in another building where there is a specific procedure to see the photos. I followed the process and a few days later I was standing in front of dozens of photos from the period of the construction of the first—and only—Greek nuclear research facility, “Demokritos.”

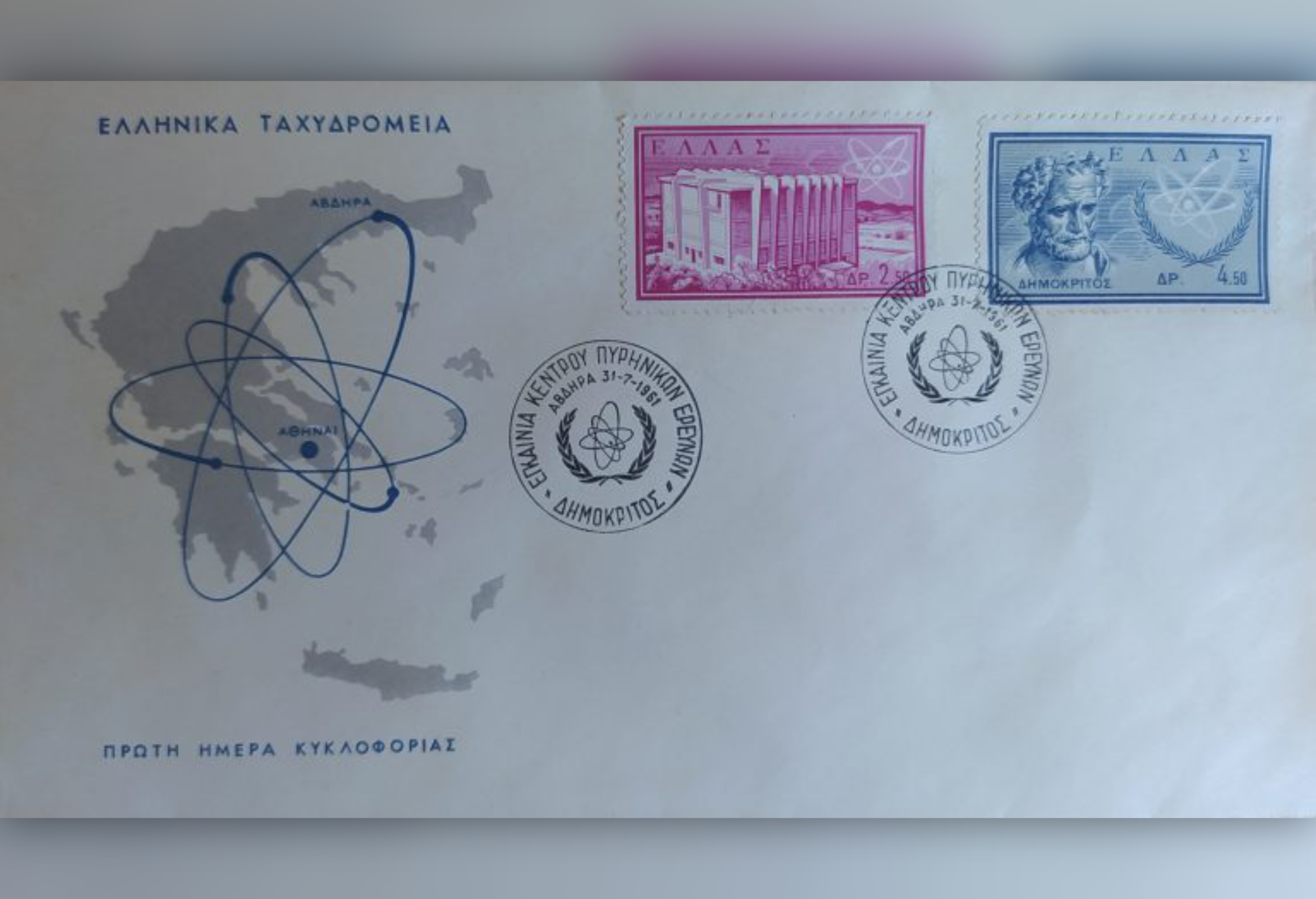

Back to Spanidis’ apartment and our conversation. After informing me about the existence of the photos, he asked me to wait a minute; he wanted to bring me something. He returned holding the second gift: two identical postal envelopes. On these were two different postal stamps, two identical seals, and a map of Greece which was surrounded by an ‘atomic’ emblem. I asked if I could take a picture of these envelopes but Spanidis generously gave me both as a gift, saying that he still had several of them. This story is indicative of the fact that oral history is not just merely complementary of the official archival research. On the contrary, through the process of conducting oral history and interviews, new archival material may come to light (as with the two envelopes) or the researcher can be alerted to the existence of available archival material that he did not have in mind (as with the photos at ELIA).

But in what follows I want to focus not on the enormous value of oral history in general but on the unusual archival material I so unexpectedly received: the envelopes. Looking at them, the first thing that catches our attention are the two colored stamps. Stamps are probably the smallest official government documents one can find. The issue of a stamp, from its design to its final circulation, is a matter of state supervision. Undoubtedly stamps are designed to accurately convey tiny messages. As Jack Child in his study of the political and cultural significance of postage stamps in Latin America notes, “these messages are frequently political in nature, involve national cultural identity, and impact a country’s citizens as well as the image that is projected abroad of that country.”[1] Indeed, postage stamps and postal envelopes travel both inside and outside the issuing state. Therefore, they also function as silent but valuable ambassadors of the country abroad.

This envelope seems to have been issued in 1961 on the occasion of the official opening of the Greek Nuclear Research Center. The two stamps too are obviously related to atomic energy. On the first, we see an imposing building above which the word HELLAS (Greece) appears in capital letters, while on the top right there is an atomic emblem with the orbits of electrons. We easily understand that this is not just any building but that which housed the first nuclear research reactor that operated in Greece, as a result of the US-Greece bilateral agreement under the American program “Atoms for Peace.” On the second stamp, we see the figure of Democritus, the Greek philosopher who formulated one of the earliest atomic theories in the 5th century BC, and next to him another atomic emblem. In fact, the Greek nuclear research center was named “Demokritos” and, as was stressed in the Bulletin of the International Atomic Energy Agency at the time, “the Greek authorities could hardly have chosen a more appropriate name for their atomic energy center.”[2] Although Greece had rather timidly taken up nuclear research just a few years before, using the heavy heritage of their Greek ancestors, Greek scientists hoped to reclaim national scientific pride and revive the country’s ancient glories. By projecting the state-of-the-art, modernist building of the nuclear reactor, the Greeks declared in all directions their proud entry into the atomic age.

The same pattern of combining the ancient heritage with progress can be found in the other two elements of envelope. The two identical seals read “Inauguration of the ‘Demokritos’ Nuclear Research Center,” there is again a schematic atom (surrounded by crossed olive branches), and just above that the inscription “Abdera, 31-7-1961.” Abdera, the Greek polis in the prefecture of Xanthi in Thrace, was Democritus’ birthplace. Based on this seal, one would expect that on July 31, 1961, an inauguration ceremony took place in Abdera. However, there is no archival record that confirms that this happened. While July 31, 1961 was the day when the Greek nuclear center was officially inaugurated, this event of course occured not in Abdera but in Agia Paraskevi, a suburb of Athens. Still, the word “Abdera” on the seal indicates that even if both the ceremony and all the scientific activities of the nuclear center took place in Athens, Abdera, home of Democritus, served as reference point to signal the historical advantage of Greece in the atomic sector.

Then again, the emblem inside the seal tells another story. One would expect to see the emblem of the Greek Atomic Energy Commission in the center of the seal, but this is not the case. Instead, the schematic atom surrounded by the crossed olive branches used by the United Nations is the emblem of the International Atomic Energy Agency. Although the IAEA officially started operating in 1957, it had taken three years for this emblem to be chosen.[3] On June 30, 1960, the IAEA sent a circular to all its member states informing them of the design of its emblem and seal, as adopted by the Board of Governors on 1 April 1960.[4] Of course the IAEA never asked its member states to adopt the Agency’s emblem as their own. However, Greece, which had been a member of the IAEA since 1957, considered that in this way it would emphasize its participation in the newly established organization, thus securing a presence in the nuclear world.

This wish is even more evident in the third and last element of the envelope, the map. The map of Greece is here congruent with the IAEA’s emblem and seal. At the core of the symbol is Athens, the capital of Greece and headquarters of the Greek Atomic Energy Commission, while one of the dots that symbolize the electrons appears at the very location of Abdera. The other three electron dots were identified with other cities or islands in Greece without being named. The message is clear: the country’s nuclearization and its connection to the IAEA would create a network throughout Greece. Centered on modern Athens and with reference to Abdera, i.e., the glorious ancient past, the peaceful uses of atomic energy would affect every corner of Greece. This message had to be heard both domestically and abroad, both by experts and the general public. And what is the best way to deliver an important message if not by means of a postal envelope?

[1] Jack Child, Miniature Messages: The Semiotics and Politics of Latin American Postage Stamps (Duke University Press, 2008), p. 2. For the role stamps play in shaping and reflecting national identity see also David Scott, European Stamp Design: A Semiotic Approach to Designing Messages (Academy Editions, 1995). For an overview of how territorial changes are reflected through stamps in the case of Greece see Konstantinos Tsitselikis, Borders, Sovereignty, Stamps: Changes of Greek Territory, 1830–1947 (Idryma Aikaterinis Laskaridi, 2021) [in Greek].

[2] Anonymous, “Report on Greece: Establishment of an Atomic Center,” IAEA Bulletin, 1959, 1(2): 9-10, on p. 9.

[3] For the very interesting story of the genesis of the IAEA emblem, see Paul C. Szasz, The Law and Practices of the International Atomic Energy Agency (International Atomic Energy Agency, 1970), pp. 1001-1003.

[4] “The Agency’s Emblem and Seal,” INFCIRC/19, 30 June 1960, IAEA Archives.